I transferred back onto the Finnmarken this morning after working a few hours on the Gateway; and with the Taurus not yet on site from the last cyclone demobilization, I’ve had the afternoon free to delve deeper into the lives of sea snakes. Although I had to wait several hours after jumping ship for my laptop power cable to catch up with me; in my haste I left it behind in the MFO cabin on the Gateway.

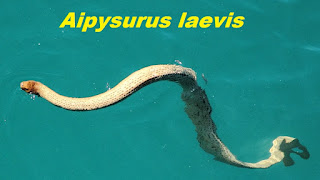

Apparently, sea snakes were one of the first marine fauna noted by early European explorers to Australia (New Holland as they knew it then), particularly in the northwest where numerous species are found (and where I happen to be located). Turns out our old pal William Dampier was one of the first to describe their presence in northwestern Australia during his visit in the early 18th century. The first formal description from an Australian specimen was of Aipysurus laevis a century later in 1804. Commonly known as the Olive Sea Snake, it is a species that I often spot basking in the sun around the spoil grounds, and which happens to be one of the most aggressive in the region. In fact whenever the Gateway’s massive 100 meter hull passes by one at the surface, it will typically hold its ground more than any other species observed, as if it’s sizing us up. I have no doubt its venom could reek havoc on the entire crew, but that steel hull may pose a problem at getting to them (although I wouldn’t put it past any Australian, sea snake or otherwise). The other common species found around Barrow, Astrotia stokesii and Hydrophis elegans, may not be as aggressive, but are amongst some of the largest sea snakes in the world; stretching over 2 meters in length.

Apparently, sea snakes were one of the first marine fauna noted by early European explorers to Australia (New Holland as they knew it then), particularly in the northwest where numerous species are found (and where I happen to be located). Turns out our old pal William Dampier was one of the first to describe their presence in northwestern Australia during his visit in the early 18th century. The first formal description from an Australian specimen was of Aipysurus laevis a century later in 1804. Commonly known as the Olive Sea Snake, it is a species that I often spot basking in the sun around the spoil grounds, and which happens to be one of the most aggressive in the region. In fact whenever the Gateway’s massive 100 meter hull passes by one at the surface, it will typically hold its ground more than any other species observed, as if it’s sizing us up. I have no doubt its venom could reek havoc on the entire crew, but that steel hull may pose a problem at getting to them (although I wouldn’t put it past any Australian, sea snake or otherwise). The other common species found around Barrow, Astrotia stokesii and Hydrophis elegans, may not be as aggressive, but are amongst some of the largest sea snakes in the world; stretching over 2 meters in length.  Like any true aquatic animal, they’ve evolved a suite of adaptations that allow them to thrive in an aqueous medium. Similar to whales and seals, sea snakes have a pair of valvular nostrils that must be actively opened for respiration, allowing for a tight ‘seal’ during dives. These nostrils are situated higher on the snout than those of terrestrial snakes, making a breath at the surface just that much easier. Given a few million or more years the nostrils may migrate to the top of the head like a whale’s blowhole. Sea snakes have broad laterally flattened tails providing propulsion when whipped back and forth. In some species much of the body is also laterally compressed, like a ribbon, to aid in swimming. Not a necessity, as terrestrial snakes are very capable in the water, but definitely an advantage. Surprisingly, a sea snake, given a motive or possibly a sense of adventure, could actually follow a humpback whale on a 100 meter dive and stay submerged with a sperm whale for up to 2 hours. They can achieve this feat partly by absorbing oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide through their skin, a process known as cutaneuos respiration (skin breathing). And of course since the body chemistry of reptiles is far less salty than the oceans, sea snakes can secrete salt from a glad in their lower jaw. These along with countless other adaptations similar to those found across the animal kingdom from marine mammals to birds, opened up a whole new niche to the traditional snake; and have given me something to look at during my 12 hour shifts of boredom.

Like any true aquatic animal, they’ve evolved a suite of adaptations that allow them to thrive in an aqueous medium. Similar to whales and seals, sea snakes have a pair of valvular nostrils that must be actively opened for respiration, allowing for a tight ‘seal’ during dives. These nostrils are situated higher on the snout than those of terrestrial snakes, making a breath at the surface just that much easier. Given a few million or more years the nostrils may migrate to the top of the head like a whale’s blowhole. Sea snakes have broad laterally flattened tails providing propulsion when whipped back and forth. In some species much of the body is also laterally compressed, like a ribbon, to aid in swimming. Not a necessity, as terrestrial snakes are very capable in the water, but definitely an advantage. Surprisingly, a sea snake, given a motive or possibly a sense of adventure, could actually follow a humpback whale on a 100 meter dive and stay submerged with a sperm whale for up to 2 hours. They can achieve this feat partly by absorbing oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide through their skin, a process known as cutaneuos respiration (skin breathing). And of course since the body chemistry of reptiles is far less salty than the oceans, sea snakes can secrete salt from a glad in their lower jaw. These along with countless other adaptations similar to those found across the animal kingdom from marine mammals to birds, opened up a whole new niche to the traditional snake; and have given me something to look at during my 12 hour shifts of boredom. Speaking of boredom, it would appear there’s a sail on the horizon (not sure if that makes sense but I wanted to use it). I have just 2 days left at Barrow Island before I fly back to the east coast. Not Boston but the other east coast, Brisbane, for 2 more days of surf. By my calculation that’s only 4 days to go in Australia, not counting the time in the air. I may need a few moments to decide what I think about that…

Interesting info on the snakes! I like the countdown!

ReplyDelete